Fact v. Analysis

Do you know the difference?

Do you know the difference?

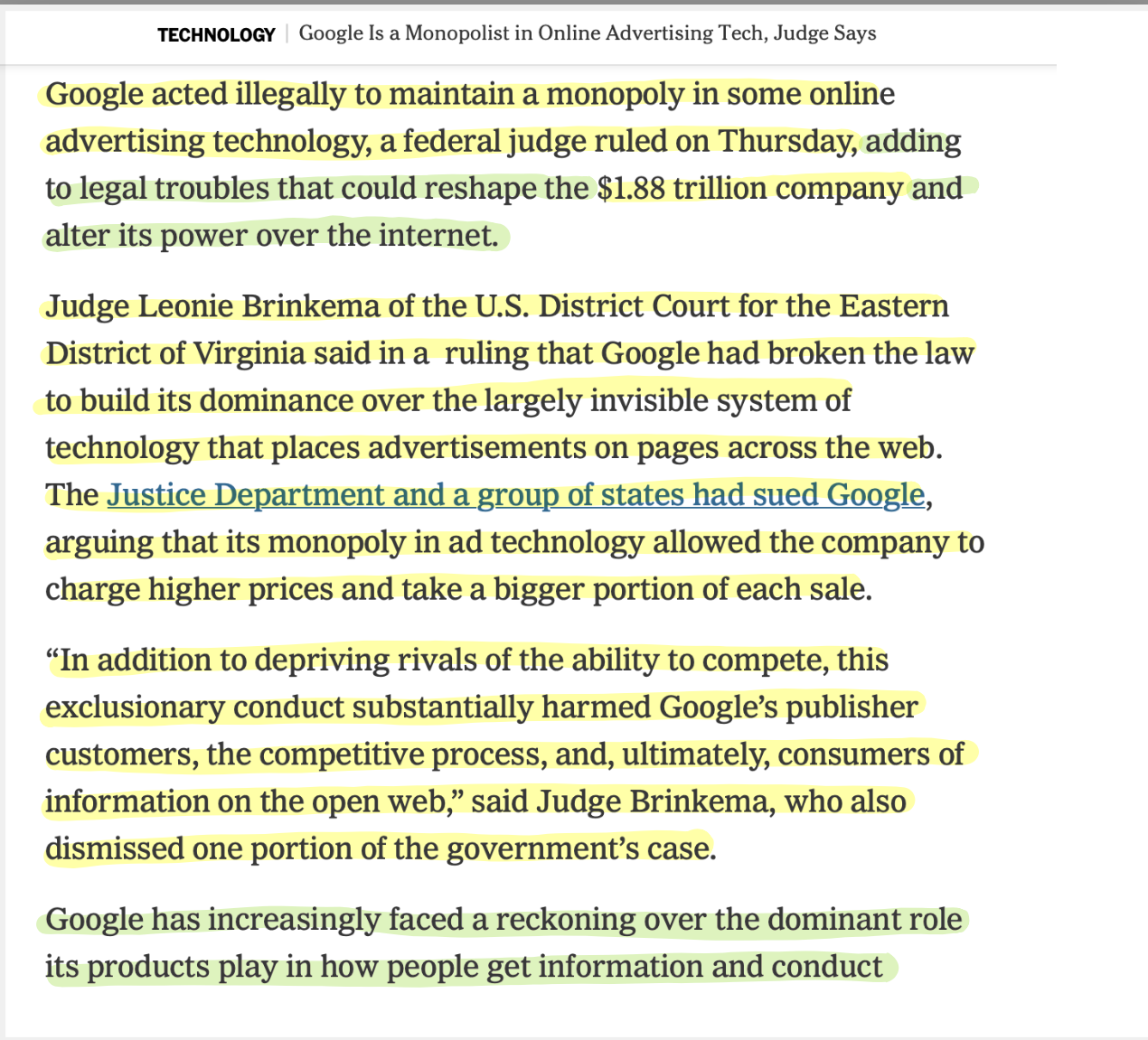

One of the things I try to teach my students is to differentiate between "facts," and analysis especially when reading news. I am aware of the debate around facts and not going to take it up in this post. But assuming we can all agree what a fact is, take a look at this randomly chosen news article. I pasted the first few paragraphs of the top story on the New York Times website at the time of writing. I have no opinion on this issue.

If you read this news coverage, can you spot the "angle" taken by the reporter, their interpretation of the facts? That is the analysis.

The "facts" are the details on which the analysis is based. I'll color code them for your benefit. Yellow are "the facts" and green is "the analysis."

Because this was the opening of an article, there were more "facts" than analysis. I would guess that deeper into the article the ratio changes. But as this is for illustrative purposes, I didn't worry too much about that.

Things I categorized as facts: summary of language of the legal opinion, people who said statements, size of company, background of case.

Things I categorized as analysis include: conclusions drawn from the facts presented (ie: a reasonable person could draw a different conclusion from that same information), characterizations of larger periods of time (which reasonable people could disagree about, even if drawing from the same "facts").

You could make a reasonable case that the parts of the legal opinion which were quoted by the author constitute analysis in part, because they are picking out some language as more important than other language from a larger document. But in general, if they are quoting from a document, and that document actually contains the quote that is being quoted, we can think of it as a fact unless it grossly misleads the reader as to the main content of the document of interest.

Sometimes my undergraduates misunderstand articles like this. They think that coverage of this legal outcome would itself constitute bias. They think that reporting on the outcome of the trial is agreeing with its outcome. But that is not the case. Reporting on a legal case is itself a reasonable basis for a news article. Drawing attention to a legal opinion of consequence is not the same thing as endorsing it (that's why back in the Twitter days everyone wrote "retweet is not endorsement" in their bios).

News sources do often endorse or oppose legal opinions, but they do so on the editorials page. In this article, the author made reference to the fact that the New York Times is not neutral on this issue (it made explicit the paper's conflict of interest) but it still chose to report on the story in a news article (separate from any coverage it might offer in its editorial page). It is reasonable for a news source to report on an issue of interest to it. By identifying the conflict of interest, it alerts the reader to be vigilant, to assess more stringently than they otherwise might if they agree with the conclusions that are being drawn.

Beyond conflicts of interest, the main reason I recommend that readers differentiate between these different types of information is because journalists frequently do not demonstrate their analyses with the facts that they provide. Whether due to poor writing, poor editing, limited resources, limited space, or actual bias, analysis is often not supported by the facts provided. If you haven't differentiated between the facts and the analysis, it can be easy to assume that the facts underpin the analysis.

In the example here, I do think that much of the analysis is reasonable. If Google is broken up, that would obviously "reshape the company." But in order to demonstrate that the company had "increasingly faced a reckoning," the author of the piece would need to tell the story of Google's legal troubles in a convincing way, demonstrating that there has actually been an increase in Google's legal troubles over time. In the actual article, the author only references one other legal case that ruled against Google. To me, this doesn't quite demonstrate the argument, but as I know very little about this case I would actually have to investigate more to decide my opinion. This approach therefore helps the reader to identify the types of questions they might ask as a follow-up to an individual news story. In fact, the main conclusion you should draw after reading any news story is "I need more information," but the reporting in the story often helps you to determine what types of information you need.

[An aside, Rob Bell did an interesting episode of his podcast "the RobCast" in which he argued for "cleaning up the clicks." Around minute 17 he described in greater detail what this means about consuming media. He didn't mean to stop reading news, he meant to be very strategic in how you read, not blithely following one link to another but thinking critically for yourself. In yesterday's post, for example, my own curiosity about how Sebastian Gorka defines terrorism led me to find a copy of his dissertation, in which he explicitly claims that defining an action as a terrorist act requires an act of violence. I would never have found that if I had just read stories about Gorka prepared by others, because no one else had made that connection. Being an active reader leads us in novel directions we might not otherwise have gone and gives us a unique viewpoint on even well-reported stories.]

Returning to the article on Google, the article ends with a quote that offers a totally different interpretation of the facts than the one provided in the story. It concludes, “Google’s conduct is a story of innovation in response to competition,” Karen Dunn, Google’s lead lawyer, said in her closing argument." This gives the reader an alternative interpretation of the facts provided. Is Google a monopoly? Or is Google innovative? The reader is forced to reckon with these two views and to decide for themselves, since they were both provided. This is a common approach taken by the New York Times. The final line of articles in the paper are often provocative and meant to be thought-provoking. This differentiates it from news outlets which taken one editorial line consistently.

The next time you notice some conclusions drawn in an article (or blog post!) that do not seem to be well-represented, consider printing it out and getting out your highlighters. What are the facts that are presented? Whose voices are offered? Whose voices are not offered? How does the author of the piece analyze the "facts" provided? Would you have drawn the same conclusions if the article had been written purely to summarize events, and not to offer an interpretation? You can seek out additional information through selective searching, or through targeted conversations after you get a sense for what you know and what you still need to know.

This form of active reading is what a political science degree teaches students, but all citizens benefit from cultivating it, especially in the current media environment with heavily partisan news coverage. At the end of the day, while most reasonable people agree on the relevant "facts," the interpretation is up to each person. An informed public does not accept the conclusions drawn from others, but draws its own conclusions from a systematic analysis of the available information. As a result, many people must be selective about what news stories they follow. It is simply not realistic to deep-dive every issue.

My general rule of thumb is the angrier I am by the end of the piece, the more attention I give the issue. Our bodies know our values, and help us to identify our priorities, even when our minds have been conditioned by socialization. It's easy to be discouraged by how many of our fellow citizens are passively taking in information. But it's not our responsibility to address their media hygiene. We are only responsible for the integrity of our own pursuit of knowledge, and increasing our awareness of when we are reading a journalist, scholar, or "expert's" analysis is a great step toward an ethic of knowledge consumption worthy of the democracy we all seek to create.