Lessons I hope we learned from the 2001 AUMF

AKA All I want for Christmas is a limited (or repealed) AUMF

AKA All I want for Christmas is a limited (or repealed) AUMF

As talk of war with Venezuela fills the airwaves, I find myself writing an unlikely Christmas list – the restrictions that a responsible Authorization for the Use of Military Force would possess. Setting aside the fact that there is little support for a military conflict among the American people (25%), and that I personally oppose conflating criminality and terrorism - which the President’s actions in the Caribbean do (as Dahlia Lithwick’s recent interview on Amicus with Malcolm Nance makes clear), if the US is barreling toward a confrontation with Venezuela, let’s do it legally.

Quaint, I know.

Most people will remember from third grade that Congress has the power to declare war, and many have likely followed the disaster of the 2001 Authorization for the Use of Military Force (AUMF), passed in the early days after 9/11 based on a number of faulty assumptions, foreseen by only one member of Congress (God bless Barbara Lee).

The 2001 Authorization itself is only sixty words: “That the President is authorized to use all necessary and appropriate force against those nations, organizations, or persons he determined planned, authorized, committed, or aided the terrorist attacks that occurred on September 11, 2001, or harbored such organizations or persons in order to prevent any future acts of international terrorism against the United States by such nations, organizations, or persons.”

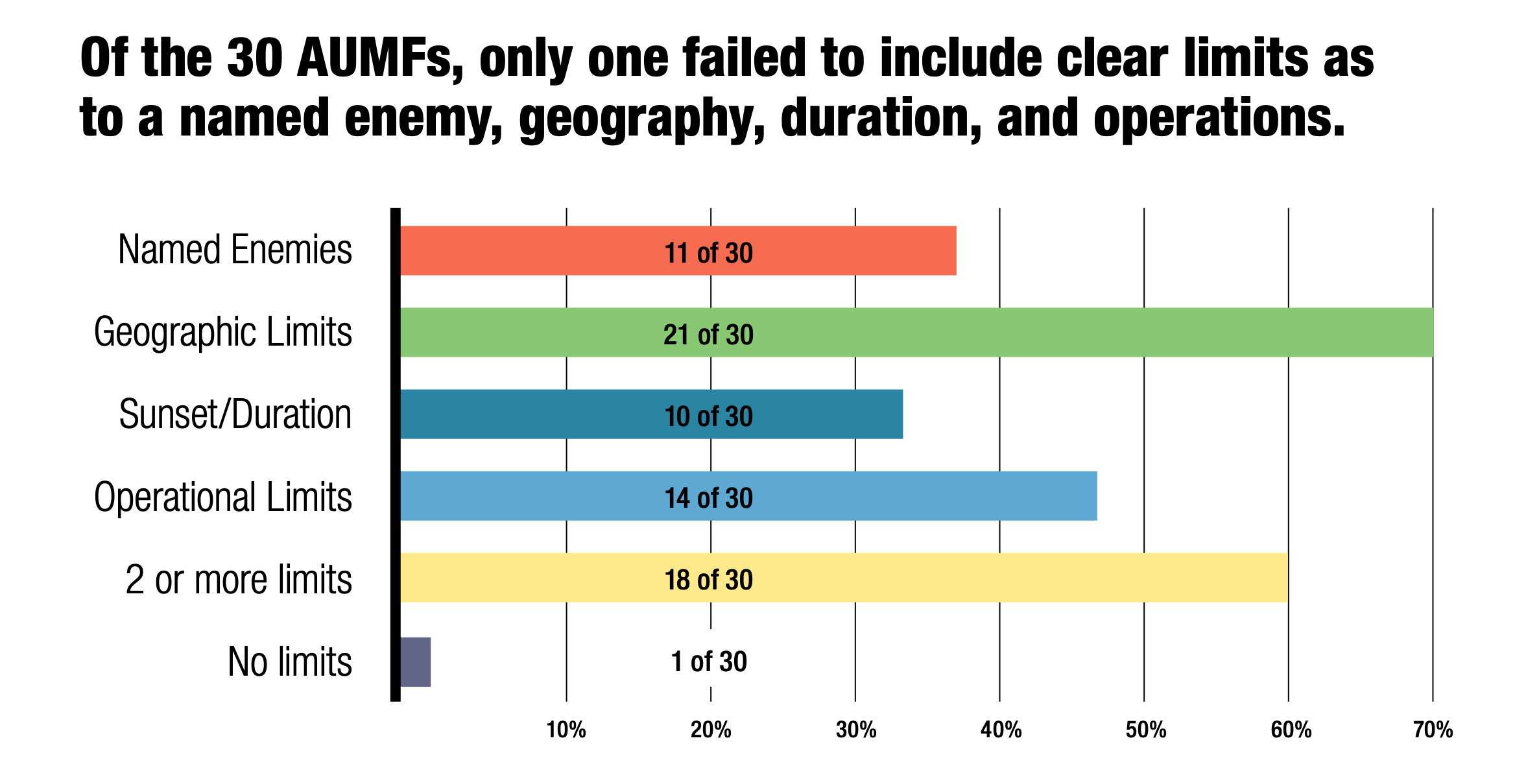

Despite its brevity, the authorization has been used for a range of actions by all Presidents of both parties, from drone strikes against groups that did not exist in 2001 (like AQAP or al-Shabab) to the killing of American citizens abroad without trial. This unchecked power was without precedent in American history. As this report from the (Quakers’) Friends Committee on National Legislation makes clear by comparing all authorizations for the use of military force in American history since 1776, only the 2001 AUMF lacked named enemies, geographic limits, operational limits and time duration limits. The current administration’s frequent reference to “narco-terrorists” (is Ronald Reagan in the house?) appears to be an effort to stretch the AUMF even further, over a conflict it most certainly was not intended to address.

Citation: FCNL Education Fund. September 2024. "Unchecked War: The 2001 Authorization for Use of Military Force 'Blank Check' in historical context."

It would be my preference that Congress would both repeal the 2001 AUMF (as Senator Tim Kaine has been arguing for years that we do) and explicitly prohibit military operations in the Caribbean and in Venuezula, but if it is not going to do so, Congress would do well to exercise its powers to limit the scope of the current President’s ambitions with a narrow authorization with the following characteristics:

1. The authorizations must define the enemy – There has been considerable confusion over whether the enemy that is being targeted are drug traffickers or the Maduro regime. The creation of an AUMF would be a good time to clarify this confusion. The 2001 AUMF failed to make clear its enemy. In fact, the AUMF did not use the language of “enemy combatant” at all, but the Bush administration claimed that the law allowed for the torture and rendition (moving to a different location ie: Guantánamo) of those captured under such a designation. It created the category in an attempt to not use the term “prisoner of war” thereby avoiding the US’ obligations under the Geneva conventions, among other laws. While those captured did represent an ambiguous category – they were not the uniformed soldiers of a nation state, the creation of a category to avoid international obligations resulted in significant litigation (such as Hamdi v. Rumsfeld) that could have been avoided by Congress addressing the issue directly. The administration also created a category “Associated Forces,” immortalized in the Radio Lab podcast episode “Sixty Words”, that has covered a range of groups whose “association” with al-Qaeda is thin if not non-existent. The experience of the 2001 makes clear that we must define the enemy.

2. The authorization must have time limits - Authorizations must define the length of time they are empowering the president to wage war. The 2001 AUMF is still active. It was employed as recently as in 2024 by President Biden to strike Iranian militias in Iraq. For a graphic of the global scope of conflicts that have been engaged under the 2001 AUMF, see this handy tool from the International Crisis Group. Time limits allow Congress to provide oversight over Presidential action AKA to fulfill its Constitutional mandate. A new authorization for such an unnecessary conflict should require re-authorization every thirty days.

3. The authorization must name geographic limits - Twenty years from now do we want a war waged in the South Pacific under an authorization passed to address the drug trade in the Caribbean? If not, then Congress needs to set geographic limits now.

4. The authorization must have a clear military objective – The wars in Iraq and Afghanistan clearly demonstrated that in the absence of clear objectives, even the mighty US military can flounder. What exactly is the objective that we are trying to achieve? Are we interrupting the drug trade? Are we pursuing regime change? By specifying it in the authorization, it will be easier for Congress to make the case that the conflict has concluded when the objective has been met. It will also force the President and his administration to make clear their objective. The 2001 AUMF should have taught us that the objective must be possible to achieve. It is high past time that the US admits that a “War on Terror,” cannot be won, and in fact may even create more terrorists.

Only Congress can give me the Christmas gift I long for, protection from another forever war that President Trump promised in his campaigns he would never start. But with the House adjourned avoiding the people’s business yet again, I fear the worst, not only for my Christmas list, but for American credibility, the American pocketbook, and American military personnel.