The War over the definition of terrorism

The rhetorical conflict between anti-ICE protestors and the Trump administration is a conflict that has been ongoing in language for more than two hundred years.

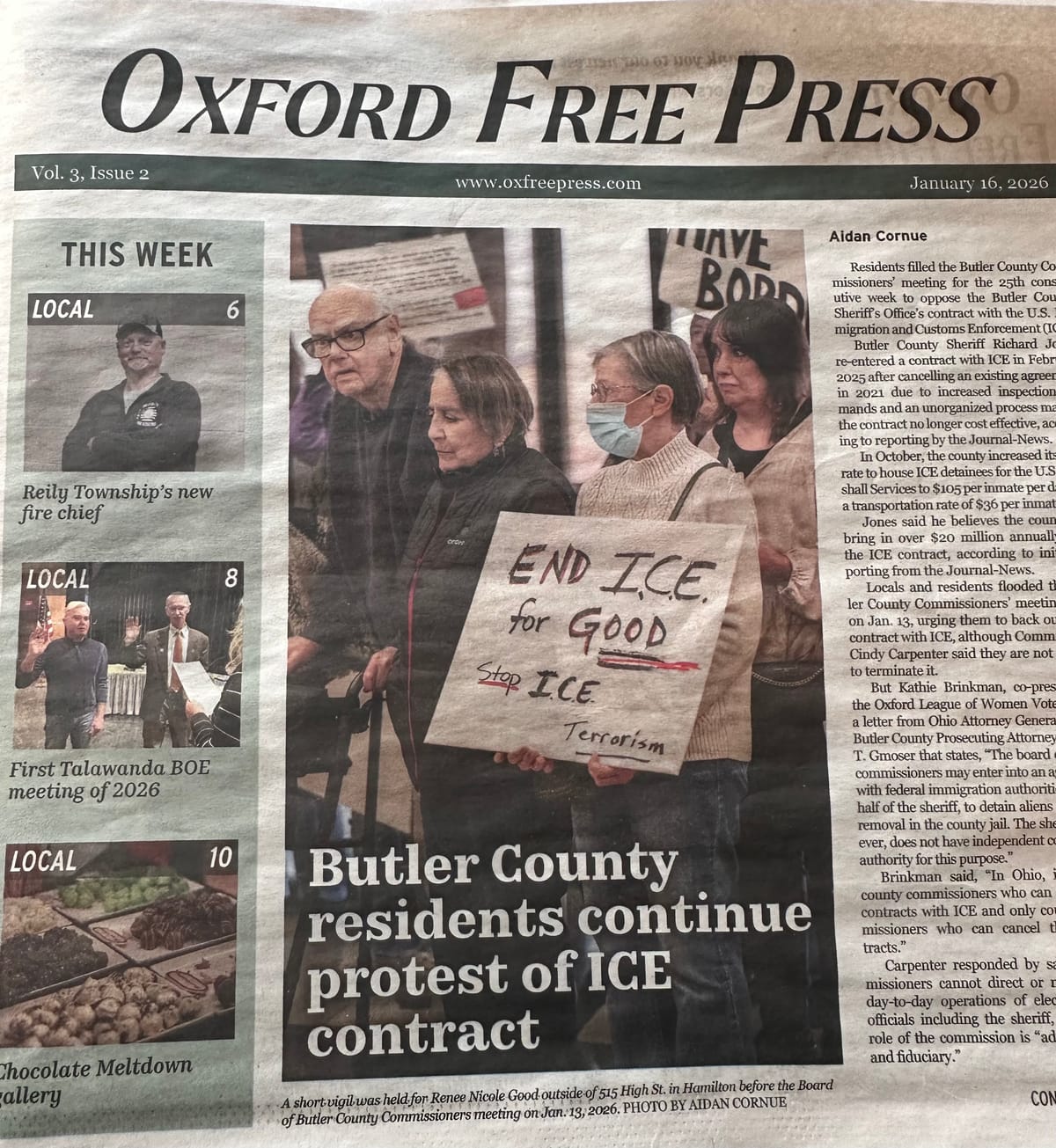

On Sunday morning, I arrived at the coffee shop to work. Sitting on the table where I sat down was a copy of the Oxford Free Press, a local newspaper. The headline read, “Butler County residents continue protest of ICE contract,” a story about how residents were protesting the local sheriff’s contract with ICE to detain immigrants in the country jail.[1]

The picture was of a demonstrator whose sign read “END I.C.E. for GOOD. Stop ICE Terrorism.” Both the words Good and Terrorism were underlined, both were a play on words. The first word "Good" referred to the name of the 37-year-old ICE watcher murdered by an ICE officer in Minneapolis in early January. But the second term was also wordplay. The Border “Tzar” Tom Homan, the Secretary of Homeland Security Kristi Noem, and other members of the administration have accused the woman who was killed of “domestic terrorism.”[2] The protestor was reclaiming this term and asserting that it is ICE (and not Good) that is responsible for terrorism.

The accusation of engaging in “domestic terrorism” has become a political football under the Trump administration. A recent article in The Hill explored this idea. It was titled “As a veteran of the ‘War on Terror,’ I have no idea what a terrorist is anymore.”[3] The author, Jos Joseph, remarked, “As a veteran of the ‘Global War on Terror,’ I have seen the Trump administration use the word terrorist to describe Renee Good, any non-Republican protestor in the U.S., captured Venezuelan ruler Nicolas Maduro, civilians in Gaza, Antifa, Democrats, and just about anyone else that he doesn’t like.” He concludes, “By Trump and company’s definition, anyone in America is now a domestic terrorist.”

The history of the word "terrorism"

The rhetorical conflict ongoing between anti-ICE protestors and the Trump administration is a conflict that has been ongoing in language for more than two hundred years. On one side are those who assert that terrorism is committed by the state against innocent citizens. On the other are those who assert that terrorism is used agains the state. Does terrorism refer to unjustified state-sponsored violence against citizens (as anti-ICE protestors use the term)? Or does terrorism refer to violence against agents of the state (as Trump administration officials assert)?

The first usage of the term "terrorism" was by someone referring to state-sponsored terror. In 1794, French politician Jean-Lambert Tallien referred to the “terrorism” of the regime of Robespierre in a speech. David A. Bell’s description of Robespierre’s use of terror sounds eerily similar to the concerns of anti-ICE protestors. He wrote, “Robespierre and his allies did not place bombs in public places. They used the police powers of a large, authoritarian state to arrest and execute their political adversaries.”[4]

Maximilien Robespierre (1759-1794) embraced a policy of “terror” against those who sought to reinstall the monarchy. He argued the use of violence was justified, even virtuous. In the words of scholar Bruce Hoffman, Robespierre “firmly believed that virtue was the mainspring of a popular government at peace, but that during a time of revolution virtue must be allied with terror for democracy to triumph.”[5] Indeed, one of Robespierre’s most famous lines asserted that terror is the required tactic for a virtuous society during revolutionary times: “virtue, without which terror is evil; terror, without which virtue is helpless.”[6]

Reducing violence through terrorism?

But the term has been used both ways. The members of Narodnya Volya, a group founded in 1878 to fight Czarist rule in Russia, proudly labeled their own acts of violence against agents of the state as terrorism.[7] In 1880, a member of the movement, Nikolai Morozov (1854-1946), titled his own treatise “The Terrorist Struggle,” arguing that violence would be necessary to overcome autocracy in Russia.[8] In the words of scholar Martin A. Miller, Morozov used the term terrorism “unabashedly [and] presents it as a positive tactic in the revolutionary combat against the Tsarist regime.”[9]

Interestingly, Morozov argued in favor of targeted assassination as a way to reduce the violence of revolutionary struggle, rather than out of a disregard for the loss of human life. He had seen how violent revolution could be, and thought that groups that assassinated key political leaders could bring about change with comparably less bloodshed. His colleague, Gerasim G Romanenko similarly thought of terrorism as “virtuous,” to borrow a phrase from Miller, and thought that the embrace of political violence could be the key to a free Russian society.[10] Thus both those who engaged in terrorism against the state and those who supported terrorism by the state against citizens insisted it was virtuous.

"The Abyss from which there is no return"

The obvious difference between nineteenth century Russia and the present day United States is that the Trump administration’s accusations against Good (and others) are based on misrepresenting the facts. Whereas Narodnya Volya was actually engaged in violence against the state, and so were willing to claim their tactics, Trump administration officials's use of the term to refer to Good are meant to suggest that she and other protestors are engaged in violence even when they are not. The New York Times has definitely argued that Good was not threatening her shooter when she turned her car to drive away from their altercation.

Beyond the Trump Administration's factually incorrect statements, the real problem is that this is not a rhetorical conflict. The president is weaponizing the institutions of the state against his perceived political enemies. He can make use of broad authorities and structure put in place to fight the War on Terror. In one example, the Joint Terrorism Task Forces (JTTFs), created after 9/11 to coordinate investigations into terrorist plots are now, after National Security Presidential Memorandum 7 (NSPM-7) being used against domestic political opponents.

For more on how JTTFs will affect dissidents, see the below conversation between Tom Brzozowski, former Counsel for Domestic Terrorism at the U.S. Department of Justice, and Lawfare's Senior Editor (and former Assistant Special Agent in Charge with the Federal Bureau of Investigation) Michael Feinberg. (I have it set to start at 39:08 where the topic of JTTFs is addressed, but I recommend the whole conversation). You can also read Brzozowski's analysis of the Bondi memo (separate from but related to the NSPM-7) here.

Brzozowski explains how JTTFs can result in innocent people being investigated by the FBI for what is actually protected speech. For the record, this conversation was posted a full week before Good's shooting, but some of what Brzozowski predicts we see taking place (with the investigation of Good's widow, for example). This is just one example of many of how the Trump Administration is making use of counter-terror tools to expand executive authority. I'll be writing about others in coming weeks.

Brzozowski ends the interview by reading remarks from Senator Church, who led the efforts to separate law enforcement and intelligence gathering after Watergate. Church cautioned, "If a dictator ever took charge in this country, the technological capacity that the intelligence community has given the government could enable it to impose total tyranny, and there would be no way to fight back."

The full quote is even more frightening. In discussing the National Security Agency (as it existed in 1974), Senator Church remarked "That [domestic surveillance] capability at any time could be turned around on the American people and no American would have any privacy left, such is the capability to monitor everything: telephone conversations, telegrams, it doesn't matter. There would be no place to hide... I know the capacity that is there to make tyranny total in America, and we must see to it that this agency [the NSA] and all agencies that possess this technology operate within the law and under proper supervision, so that we never cross over that abyss. That is the abyss from which there is no return."

People call other people "terrorists" because they want to delegitimize the other's use of violence. While historically it's true that this term has been used both to describe violence against the state and violence by the state against its critics, it's essential to note who is actually committing acts of violence and who is not. And when that violence is committed by the state against citizens (and non-citizens) for their political views, all citizens must resist it. The Trump Administration's insistence on calling all of its enemies "terrorists" creates serious concerns for first and fourth Amendment protections for citizens. While the rhetorical battle has been going on for hundreds of years, the tools the Trump administration wields, courtesy of War on Terror reforms, should give every American citizen pause for concern. As Senator Church cautioned, if we cross over into the abyss that is tyranny, we might not return.

[1] Aidan Cornue. “Butler County residents continue protest of ICE contract.” Oxford Free Press. 16 January 2026. Online version of story does not contain the same photo. Available at: https://www.oxfreepress.com/butler-county-residents-continue-protest-of-ice-contract/

[2] https://www.nbcnews.com/politics/politics-news/border-czar-ice-shooting-victim-actions-domestic-terrorism-minneapolis-rcna253425?cid=referral_taboolafeed

[3] https://thehill.com/opinion/white-house/5683729-ice-shooting-terrorism-debate/

[4] David A. Bell. “Pity is a Treason.” New York Review. 28 June 2018. https://www.nybooks.com/articles/2018/06/28/terror-france-pity-is-treason/

[5] Bruce Hoffman Inside Terrorism, Columbia University Press, 2017: p.4.

[6] Ibid. Original: “la vertu, sans laquelle la terreur est funeste ; la terreur, sans laquelle la vertu est impuissante.”

[7] Bruce Hoffman Inside Terrorism, Columbia University Press, 2017: Ch. 1 fn85.

[8] Miller, Martin A. The Foundations of Modern Terrorism: State, Society and the Dynamics of Political Violence. Cambridge University Press, 2013, p.72.

[9] Ibid p. 73.

[10] Ibid p. 74.