What makes someone a "terrorist?"

It's not what you think

It's not what you think

Many years ago, when I was a graduate student at St. John's University (I'm guessing 2006?) I took a course on terrorism. In those first few years after September 11th, 2001, there was much discussion of this term and whether it could or should be used in academia as a "concept." The definition I was taught then was relatively simple:

- An act of violence

- With a political motive

- Aimed at creating fear among the population

The definition seemed simple enough, but when I went to write a chapter for my book several years later what I found is that counter terror legislation was more frequently used by authoritarian regimes against members of the political opposition than against people who had committed violence intended to create a culture of fear. Websites that posted statements made by "terrorist" organizations, journalists who had communicated with opposition groups, and people that regimes did not like were subject to the harsh dictates that had only been approved by their legislatures because they were supposed to be used under extraordinary circumstances when state security was at risk. Instead, states around the world charged a wide range of actors with counter-terror crimes under vague pieces of legislation that did not require an actual act of violence to have been committed.

How could they do this? As detailed in my book, many pieces of counter-terror legislation use a broad definition for an act of "terrorism" that does not require an actual act of violence to have taken place. For example, Morocco's definition of terrorism adopted in the wake of the 2003 Casablanca bombings defined terrorism as acts that "are deliberately perpetuated by an individual, group or organization, where the main objective is to disrupt public order by intimidation, force, violence, fear or terror." Within two months of passing this new definition, four journalists had already been changed with terrorism related offenses simply for reporting on acts of violence.

The vague definition had other consequences. Lisa Stampnitzky's book Disciplining Terror traced the development of a field of study called terrorism studies from its beginnings in the early 1970's until the post-9/11 period. She pointed out how the vague definition of terrorism that took root in the field of terrorism studies allowed for a broad range of people to claim to be experts on the subject. As a result, the discipline had trouble policing its boundaries in the way a more traditional field like "Political Science" might be able to do.

A colleague of mine often referred to the class of "experts" claiming expertise in terrorism as "terror-ologists." This label was meant to differentiate real scholars with PhDs, language skills, regional knowledge, and location firmly in academic disciplines from those individuals who ran from terrorist attack to terrorist attack claiming expertise about a vast range of actors and territories that it would literally be impossible for one person to understand. Vague definitions of terrorism have therefore not only allowed for innocent civilians to have their civil liberties violated, it has also made it challenging for academic experts to be heard amongst the din of terror-ologists seeking to profit from the industry of terrorism prevention.

Why is this issue becoming relevant in contemporary times? Yesterday evening the Meidas Network reported that Deputy Assistant to the President AKA "the Counterterrorism Czar" Sebastian Gorda has suggested that anyone arguing for due process for Kilmar Abrego Garcia could be viewed as "aiding and abetting a terrorist" and "be federally charged." KAG is the legal resident of the US deported to El Salvador in an "administrative error." I discussed his situation in my post yesterday.

JUST IN: Deputy Assistant to the President and "Counterterrorism Czar" Sebastian Gorka says anyone advocating for due process for Kilmar Abrego Garcia could be viewed as "aiding and abetting a terrorist" and be federally charged. (h/t Philip Germain)

— MeidasTouch (@meidastouch.com) April 16, 2025 at 10:07 PM

[image or embed]

I strongly encourage you to watch the clip. Gorka argues that if you "love America" you will accept the government's argument that KAG is a terrorist. This is extremely disturbing language. Any time your government tells you that if you love your country you have to do X, Y, or Z, you should be extremely suspicious. No one gets to tell you how to love your country.

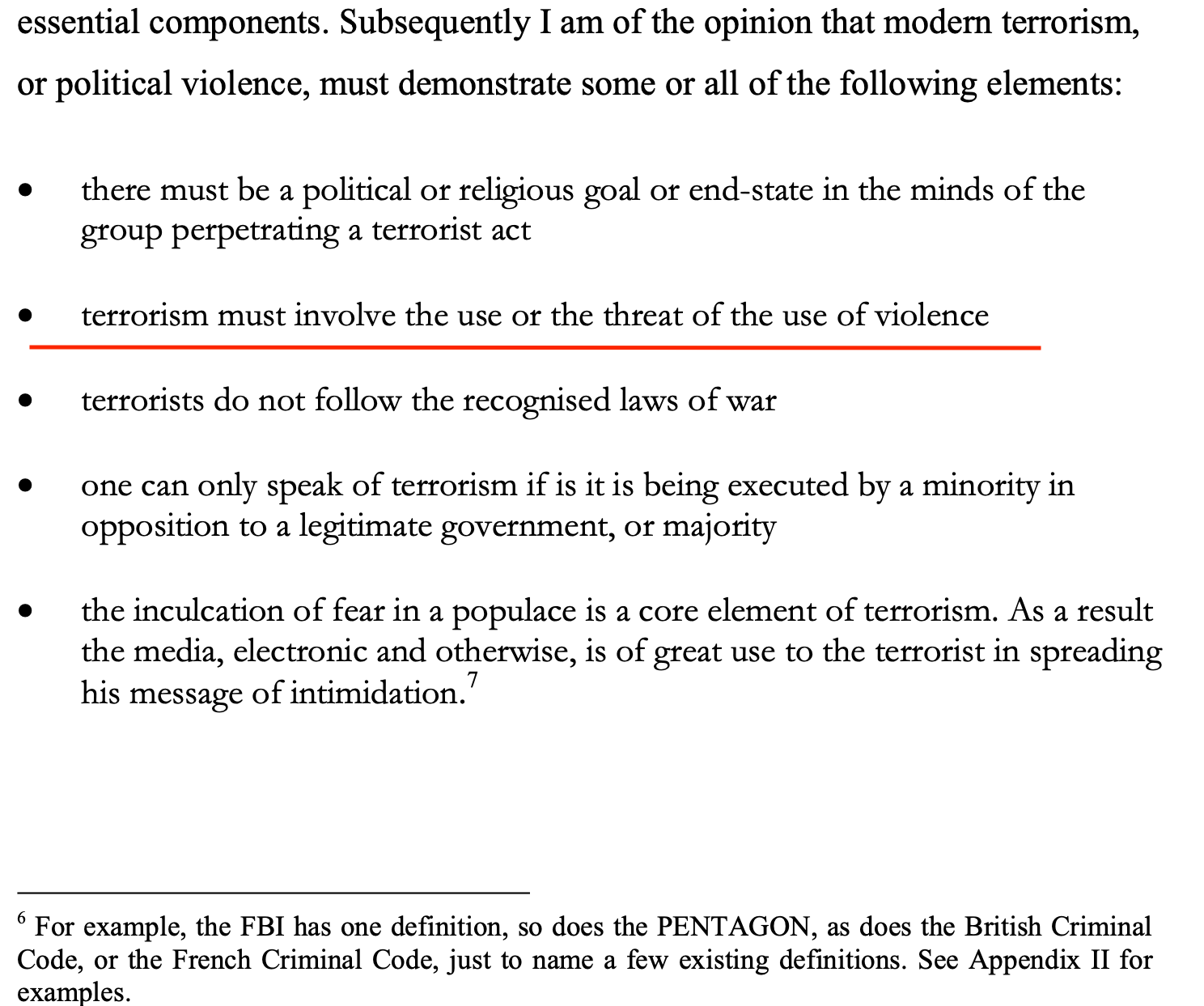

Gorka himself, in his own dissertation, argued that terrorism requires an act of violence:

There are a few points to underscore:

- Kilmar Abrego Garcia has no criminal record. There has been no evidence presented that he committed or intended to commit an act of violence. He is not a terrorist.

- KAG cannot be called a terrorist just because the administration is embarrassed that they deported a legal resident of the United States and is now under legal pressure to return him to the country.

- Calling for due process for KAG is not "aiding and abetting a terrorist." It is calling for just application of US law.

- If you are labeled a terrorist by the administration, they have access to a vast range of tools (see this description from the DOJ) that are permitted by counter-terror legislation (the Patriot Act among other pieces of legislation) that they would otherwise not have access to. That is why they are using this language.

- If the administration follows through on this threat, they would be violating the law. The US definition of terrorism requires an act of violence. See, for example, the FBI's definition: "Violent, criminal acts committed by individuals and/or groups to further ideological goals stemming from domestic influences, such as those of a political, religious, social, racial, or environmental nature."

- Your support of KAG is not an act of violence. It is not terrorism. It is patriotism.

This discussion raises a provocative question: Is the government's deportation of KAG an act of terrorism? After all, it is an act of violence intended to instill fear in a wide range of individuals in the United States. How you answer this question would depend on whether or not you allow states to commit acts of terrorism. I tend to prefer a cleaner conceptualization that labels acts of violence committed by states as human rights violations, and acts of violence committed by non-state actors with a political motive to instill a culture of fear as terrorism (or even better, political violence). There have been some scholars who have argued that states can commit acts of terorrism while others accept that states can sponsor (ie: pay for, facilitate training of) non-state actors that themselves act as terrorists. So the answer to this question depends on how you define terrorism.

In sum, the vague definition of terrorism that has plagued both the study of terrorism and counter-terror legislation has had profound implications for pro-democracy actors and political dissidents. Efforts to apply this language to US citizens who have never committed a criminal act need to be resisted vehemently to protect our basic civil liberties. The administration is using this language in order to instill fear and to gain access to a set of tools that were put in place to protect American citizens from serious threats of violence, not to protect them from legitimate forms of political opposition to government outreach and impunity.